Yesterday I visited the Beaney House of Art and Knowledge, Canterbury's main museum, library and art gallery.

It is no ordinary municipal museum. In the style of the presentation of its collection, it perhaps reflects the flamboyant personality of Dr James Beaney, the man behind its establishment at the end of the 19th century.

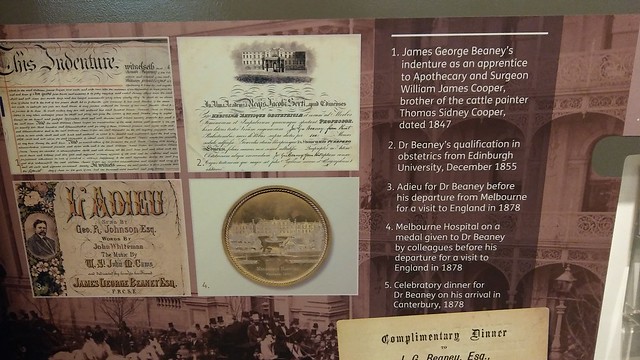

I was intrigued by his connection with Melbourne, where he migrated in 1852 in order to deal with a health condition that required a long sea voyage.

Beaney was a surgeon, politician and notorious self-publicist. He was born in Canterbury and maintained a link with the city for the rest of his life. And for posterity, through his endowment of 'The Beaney Institute for the Education of the Working Man', which he named in his own honour. He had himself risen from the working class after managing to acquire an education.

In Melbourne, Beaney shook up the medical establishment. An article in the Australian Dictionary of Biography (ADB) describes him as 'a bold surgeon, perhaps rash and rough at times, without the finesse and skill of [his contemporaries] Sir Thomas Fitzgerald and E. M. James, yet often successful when others less daring would have failed'.

He was recognised as a pioneer in the specialisations of child health, family planning and the treatment of sexually transmitted diseases. But he was just as well known for his fondness for showy jewellery, which he wore even while operating. This earned him the nickname 'Diamond Jim'.

His controversies included four inquests on patients who died after surgery. One led to his trial and acquittal for the murder of a barmaid who died after an alleged illegal abortion. According to the ADB article, he was 'rightly acquitted', in light of 'a regrettable element of professional animosity'.

Beaney had a demeanour that lent itself to caricature. His detractors described him as a 'short, podgy man' with 'pale blue, rather shifty eyes', with his hair curiously upswept to either side of his head 'like a pair of horns'.

He was posthumously criticised for not providing for surviving relatives in his will, instead favouring vanity projects like the Beaney Institute, which had to display his portrait in the main hall of the building (above). In addition, he provided £1000 for repairs to Canterbury Cathedral on condition that a memorial tablet was erected (this led to the Cathedral Dean and Chapter banning such tablets in the future).

My own view is that it can be amusing to judge people whose vanity has overshadowed their achievements but it's important to look at what their legacy has produced. In Beaney's case, a quite remarkable regional museum with quirky and creative exhibits such as the current temporary exhibition of photographs of Canterbury taken by the city's community of homeless people.