One of my family's treasures that has been passed through the generations is a set of two watercolour miniatures of my progenitors. They were painted by an itinerant artist on the Victorian goldfields soon after their arrival in Australia from Ireland in the 1850s.

I was reminded of these miniatures on Saturday when I visited the Dempsey's People exhibition at the National Portrait Gallery in Canberra.

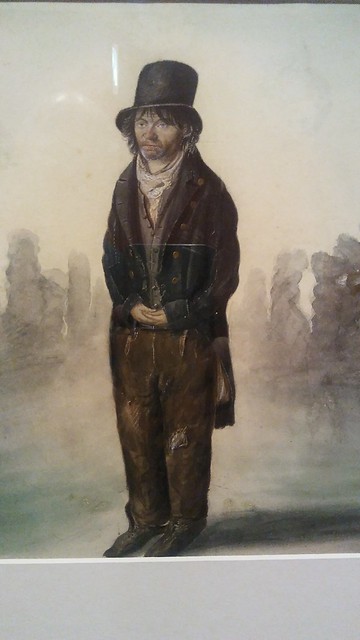

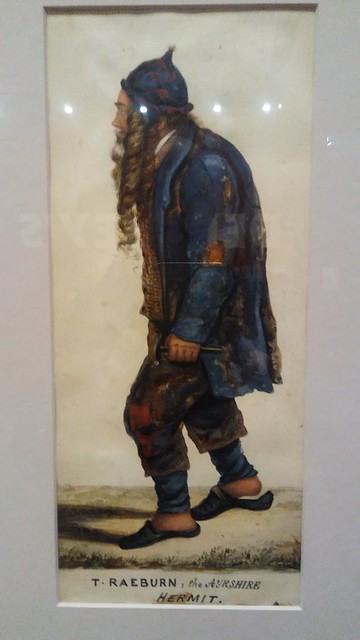

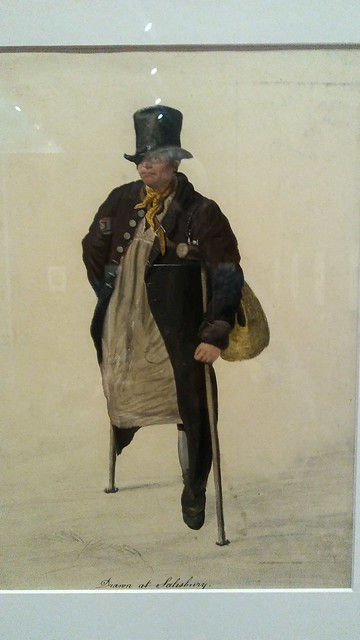

The mostly watercolour images of British street people were painted by itinerant artist John Dempsey during the first half of the 19th century. It was the era before photography put itinerant artists out of business.

As the exhibition notes put it, they were 'the real-life models of the proletarian grotesques in Charles Dickens' novels... the kind of people who came to Australia as convicts and as free settlers during the early colonial period'.

It is rare and refreshing to see portraits of people from the 18th and 19th centuries who were not the wealthy and influential celebrities of their day. It seems that it was almost an act of subversion to paint street people in a style that made them look as dignified as the nobles and rich merchants that dominate the National Portrait Gallery in London.

In particular I appreciated the paintings of the Ayrshire hermit, the Durham beggar, 'Little John' the Colchester lunatic, the maniac, and the old soldier from Salisbury. Each of them was painted in a way that made them stand tall, not reflecting the crushed demeanour and self-image that you would expect from their lowly circumstance and class. The stigma of the descriptors, lacking modern day political correctness, was turned on its head.

I was interested to read about 'old soldiers' in the notes about the exhibition. After the final defeat of Napoleon, the troops flooded home to an undeservedly less than rapturous welcome. The Duke of Wellington described them as the 'scum of the earth'. There was little work and few prospects for them in the towns and villages, where the derelict Old Soldier become a familiar figure.

This came home to me yesterday when I was talking to an incapacitated former Australian soldier who had been wounded in Afghanistan. It seems that the scant regard for 'old soldiers' is still a reality in our time. I think this applies generally to the way marginalised and dispossessed people in our community are stigmatised and represented adversely in the portraits painted by our celebrity dominated media, and - consequently - in our own attitudes.

Link: Dempsey's People