Yesterday afternoon I ventured into the Marais for one of my typically aimless walks. I like to explore back streets in particular, and never know what I will see or discover. In one of those streets I came across a mid-size museum I’d never heard of, the Cognacq-Jay.

It is among the 14 Paris museums run by the public institution known as Paris Musées. It’s billed as a museum of ‘18th century taste’, a reference to style and outlook rather than food.

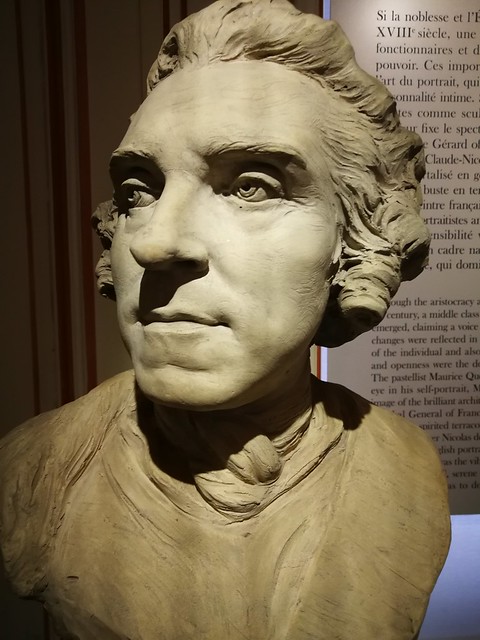

I’d never before been to a museum of ‘taste’, and most of the visitors are probably not so interested in that descriptor because it’s clear that the Cognacq-Jay’s contents are entirely paintings, sculpture and ornaments.

But it intrigued me, as I’m most interested in social history. I like viewing art works not as ends in themselves but as reflections of the lives of people and sub-cultures of a given time or place.

What distinguishes particular peoples is what they regard as being in fashion at their moment in time. That is their common taste and it is reflected in the style of their collective lives and possessions.

When entering the museum, I thought to myself that I’m not so interested in the 18th century, as it was the 20th century that most shaped my own life and culture. But I was wrong.

I learned that the 18th century was known for the diminishing influence of the church and aristocracy as all powerful entities that dominated people’s lives. There was the rise of a middle class consisting of tradesmen, administrators and artists who were claiming a voice and power for themselves.

These changes were reflected in the art of the portrait, which established the role of the individual’s own personality. Spontaneity and openness were dominant in the paintings and sculptures of the 18th century.

These people were fascinated by ways of life in other parts of Europe and beyond. Some embarked on the Grand Tour, while others were taken up with exoticism or the idea of ‘elsewhere’ (e.g. India and China) and its magic and curiosities, as well as the discovery of new species.

According to notes accompanying the displays in one room, ‘The import of new exotic products such as spices, drinks and craft objects, brought about changes in consumer habits that blended European culture with imported items’.

As I see it, the church and aristocracy were not being replaced, but instead invited to play a part in the lives of the people alongside the new influences from outside. If they chose not to play ball, they would be ignored by the mainstream.

Churches and the aristocracy can still be dismissive of taste and values other than their own, and also the blending of various spiritual and cultural influences that has become the norm. It was therefore clear to me the continuing relevance of the explosion of taste in the 18th century.