For most of May I'm in England, staying in the old Kent market town of Faversham, a few stops north of Canterbury on the train line from Dover to London. It's also on the line that proceeds from Dover towards London along the coast, through a number of seaside towns including Deal, Broadstairs, Margate and Whitstable.

While I was here last May, I discovered that it's perfectly legal to buy a return ticket from Faversham to Whitstable - one station - for just £3.90, and travel in the opposite direction, taking in the long scenic route around to Whitstable through Canterbury, Dover and all the other coastal towns, breaking the journey a couple of times along the way.

That's what I did yesterday. My stops included Broadstairs, where I visited the Dickens House Museum.

Charles Dickens would spend his summer holidays in Broadstairs in the 1850s and 1860s, in a cliff top house named Fort House, which is claimed to be the Bleak House depicted in the title of Dickens' 1853 novel.

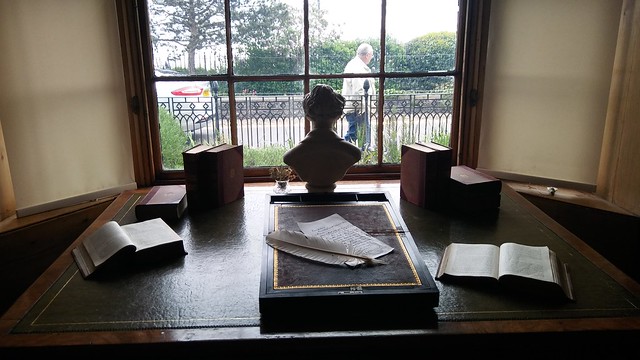

The Dickens House Museum is in the beachside home of the friend of Dickens who was the inspiration for the character Betsey Trotwood in David Copperfield. It contains items that once belonged to Dickens such as his writing box and a mahogany sideboard that he owned from 1836 to 1855.

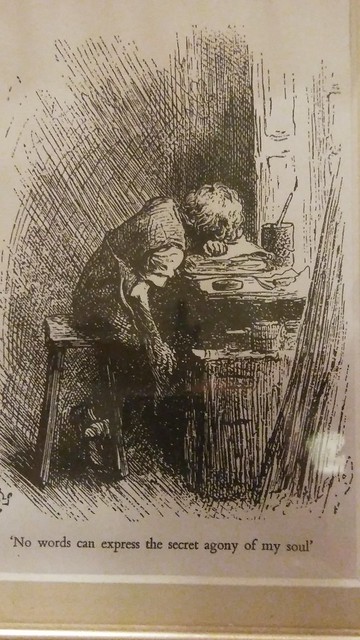

But what I found most interesting was the portrait of Dickens' London. This included his experiences as a 12 year old child working in a boot polish 'blacking' factory after his father was arrested for debt and sent to Marshalsea prison.

He was clearly traumatised by his experience of the rat infested workplace - 'the dirt and decay of the place rise up visibly before me as if I were there again'. His loneliness deepened his despair. 'No advise, no council, no encouragement, no consolation, no support, from anyone.'

It's probably fair to say that he suffered from what we now call post traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), and that this formed his outlook on life and gave him the basis of many of his novels. Later in life, Dickens used his writings to offer a social commentary that improved the lives of the poor.

The other quotation that caught my attention was from Our English Watering-Place, Dickens' 1851 eulogy to Broadstairs. It was about welcoming outsiders.

'We are a little bilious sometimes, about these days of fraternisation, and about nations arriving at a new and more unprejudiced knowledge of each other ... but it soon goes off, and then we get on very well.'

This could have been wishful thinking on the part of Dickens. Or perhaps the locals' attitudes have changed over the course of the past 116 years. In the Brexit referendum, the Thanet local government area that includes Broadstairs voted overwhelmingly to leave the EU, by a margin of almost two to one.

Moreover the local council is dominated by UKIP councillors, and former UKIP leader and vocal Brexit campaigner Nigel Farage stood for election in the local South Thanet constituency in the 2015 parliamentary elections.

On the stairs above the beach a few metres from the Dickens House Museum, I noticed a group of teenage boys speaking what seemed to be Polish or some other Eastern European language. A sign of the times that are soon to change.