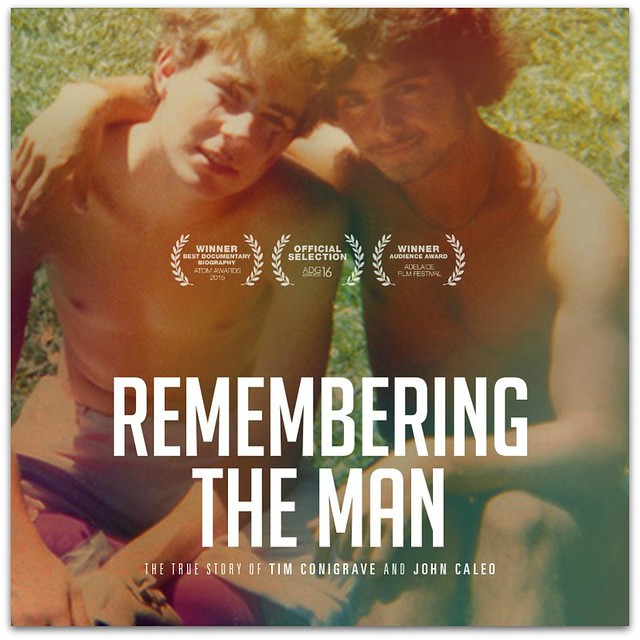

I rewatched part of Remembering the Man on iview yesterday after it was screened on ABC2 on the weekend.

It is the 2015 documentary interpretation of the tragic love story of the Melbourne Catholic schoolboys Tim Conigrave and John Caleo. They fell in love at Xavier College in the 1970s and continued their same sex relationship for most of the time until they both died of AIDS in the early 1990s.

The documentary followed Tim Conigrave's highly successful memoir Holding the Man that was posthumously published in 1995. It was later dramatised on stage (2006 and subsequent productions) and in a feature film (2015). The novel developed a legendary status as one of the '100 Favourite Australian Books' of all time. It is also regarded as essential reading for young males exploring their sexuality.

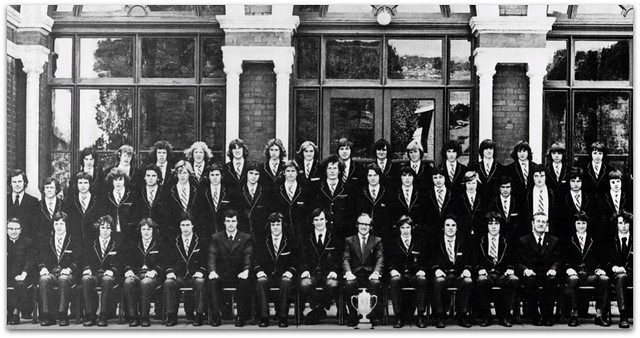

It's of particular interest to me because Tim and John were in my class at school and all of the archival footage in the first part of the film brings back memories of my own school days.

I'm currently assessing my school days, in the lead up to the 40th anniversary dinner on 1 September. Because I have mixed feelings about my school days, I wasn't sure whether I wanted to be there. I'm relieved that the decision not to attend has been made for me by the date's clash with my forthcoming sojourn in Tokyo.

I was in their class, but I was not part of Tim and John's immediate circle of friends. I was privy to few of the details of what was going on. But I knew the context very well and understand what others with preconceived notions of Catholic education at the time find hard to believe.

That is how a same sex relationship could be implicitly supported by some of the religious teachers at the school and by an ostensibly homophobic sport focused peer group. One theory is that it was because the 'renaissance man' ethos of Jesuit education prevailed at this school. This was in practice, not just in theory, and among staff and students alike.

Of course that argument is contentious and simplistic. The open minded attitude of the Jesuits at the school has as much to do with post Vatican II liberalism and confusion, and the winds of change that challenged social norms in the years that followed the election of Gough Whitlam in 1972. There's also the unexplored question of whether the attitudes of the two Jesuits as depicted in the story represented what their Jesuit colleagues were thinking at the time. Probably not.

In my early days as editor of the Jesuit publication Eureka Street in 2006, I reviewed the first stage production of Holding the Man. I wrote in celebratory terms about what I saw as the school's implicit affirmation of the school boys' same sex relationship.

When I presented the article for approval, I was requested to make changes. This was because of continuing raw emotions on the part of John's family and the fact that my interpretation of the events - and that of the play - was regarded as contentious and possibly damaging to the reputations of individuals who were still around.

I would be interested to know how such an interpretation of events would be treated by the censor eleven years down the track. There's no doubt it will be talked about at the dinner on 1 September.

Links: iview trailer website Eureka