Yesterday a friend sent me a Washington Post opinion piece about 7150 'socially minded nuns' declaring Trumpcare a moral outrage.

The article was written by E.J. Dionne, who's well known to Australians because he's often interviewed on the ABC's Radio National.

He praised the three Republican senators who thwarted Trump's plan to deprive millions of Americans of health coverage. But also mentioned the nuns' much less publicised intervention, which labelled the Senate GOP's core proposal 'the most harmful legislation for American families in our lifetimes'.

The nuns cited Pope Francis' insistence that 'health is not a consumer good, but a universal right, so access to health services cannot be a privilege'.

Dionne's point was not to argue that the nuns influenced the outcome, but that most people are not aware of how wrong religious stereotypes can be.

'This is important because religion and the political standing of believers are badly harmed by the reality that so many Americans associate faith exclusively with the conservative movement. Large numbers of young people are abandoning organised religion (and particularly Christianity) altogether. A key reason: They see it as deeply hostile to causes they embrace, notably the rights of gays and lesbians.'

It's not widely realised that some of the strongest arguments for marriage equality can be found in religious teaching about social justice. As Dionne points out, Pope Francis is insistent that the Church be associated with justice and mercy rather than cultural warfare.

I think that it can be argued that the Australian Catholic hierarchy's opposition to marriage equality is a hangover from the cultural warfare of the previous popes and that the position of the bishops is essentially out of step with the present pope.

I believe that this and many other debates are wrongly characterised as being between secular and religious interests. Rather it's entrenched interests (such as big business) against ordinary people who rely on human rights promotion for their basic survival.

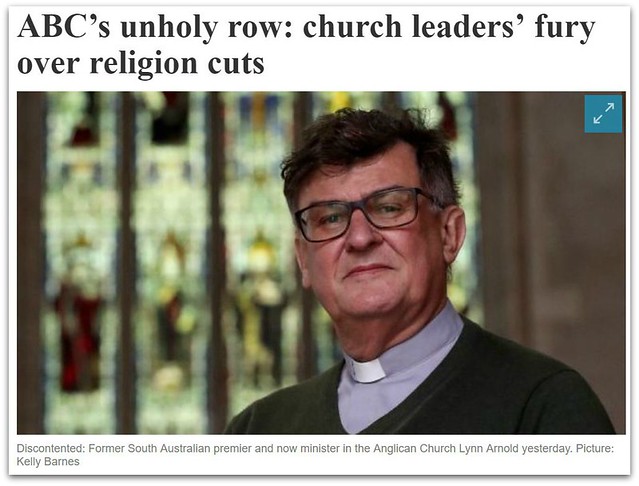

That's why the Murdoch press waged a successful campaign to discredit and remove the head of the Human Rights Commission Gillian Triggs. Yesterday the issue they chose to give voice to was the call from commercial media chiefs to reign in the public service broadcasters ABC and SBS, which take human rights reporting seriously.

It's regrettable that a surprising number of people continue to believe that religious interests line up behind the conservative establishment against the so-called socialists of the left, who are thought to be godless.

The Catholic Bishops feed that perception when they demonise the Greens, usually for opposing their own institutional interests such as Catholic education. Even taking into account the Greens' positions on issues such as voluntary euthanasia, I would suggest that the Greens are far more in line with the teaching of Pope Francis and the Catholic Church than the conservative parties that most people instinctively link to religious positions.

Links: Dionne ABC/SBS