On Tuesday I had a few hours to fill around the South Bank cultural precinct in Brisbane.

A few days earlier I had walked past the Queensland Museum. I was not interested in the current exhibition Gladiators: Heroes of the Colosseum, which I assumed was there to attract the attention of school children, particularly boys.

I had just decided against paying to see Marvel: Creating the Cinematic Universe comic superheroes exhibition at the Gallery of Modern Art (GOMA), which was seemingly presented to lure fans of popular culture.

On Tuesday I walked inside the Museum, hoping that I would find something else that would appeal to my particular interests. But no, it was mostly ancient and natural history.

There was the Lost Creatures exhibition. 'Meet strange creatures, including our very own dinosaurs, giant marine reptiles and megafauna, and marvel at the diversity and immense size of creatures from our prehistoric past.'

I challenged myself to specify exactly what it was that I wanted to see. What came to mind was social history. So I sought out the attendant, asking her if there was any social history in the museum.

She could understand exactly what I was asking and I had the sense that her taste corresponded much more with mine than that of the school age majority clientele. She said that regrettably there was almost no social history at the museum, except a few 'leftovers' from past exhibitions.

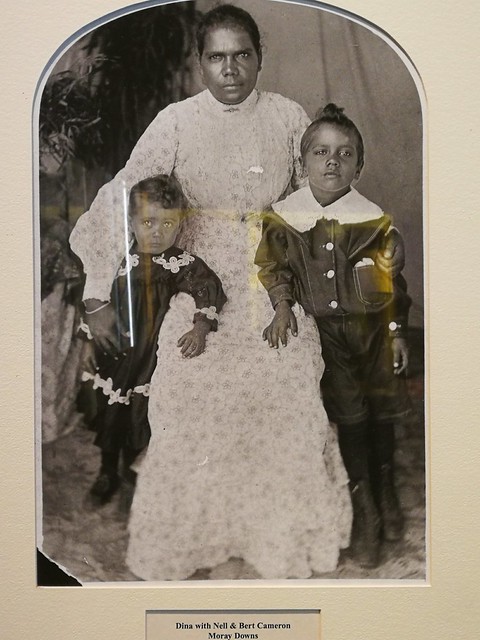

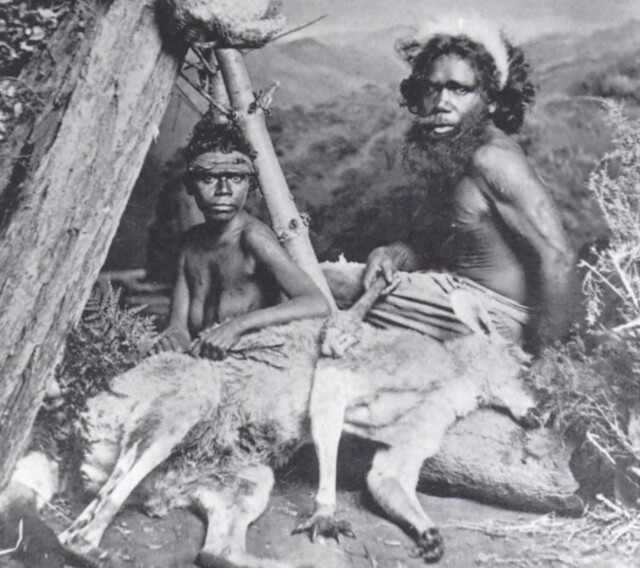

This was what I was looking for, particularly the fragments from the well received 1991 show Portraits of our Elders. It was a collection of photographic studio portraits of Aboriginal people from the late 19th and early 20th century. It was intended to demonstrate the shift from awkward and patronising depictions of 'exotic' or 'noble savage' types - a variation on the strange creatures in the natural history exhibits - to confident poses of indigenous people more in command of the situation.

There is one photo in the original collection of an Aboriginal man and woman with a dead kangaroo that was taken inside a studio in Grafton around 1873.

The most memorable print in the selection I saw was the portrait of Katie, Lilly and Clara Williams, the three aunties of curator Michael Aird's grandfather. They inspired him to create the exhibition: 'I was struck by the photograph; the beauty of my grandfather's aunties, and the confidence they demonstrated'.

The well-dressed, confident Aboriginal men and women walking into studios as paying customers was set in contrast to the bare-breasted Rosie Campbell of Stradbroke Island. Aird wrote in the exhibition's book of the more dignified covered version of Rosie in photos he saw when he visited the homes of her grandchildren on Stradbroke Island.

'Not only is she fully clothed in the photographs held by her relatives, but the families have much information and many personal memories of Rosie as a person. Among the numerous photographs the family has of Rosie from the same era in which she posed bare-breasted is one of her fully clothed in the same studio setting.'