The blemish on this week's 'beautiful set of numbers' announced by Treasurer Josh Frydenberg was wage growth.

Australia's economy is performing well, at least for now. This is due to a combination of fortuitously high commodity prices and government fiscal restraint.

But wage growth is around two per cent per year, half what it was a couple of years ago. That's the slowest sustained rate of growth since the Great Depression of the 1930s.

This interests me because I'm coming to the end of a short-term paid research task for a Sydney academic. She is comparing the diminishment of the wage system during the Great Depression to that of the present day.

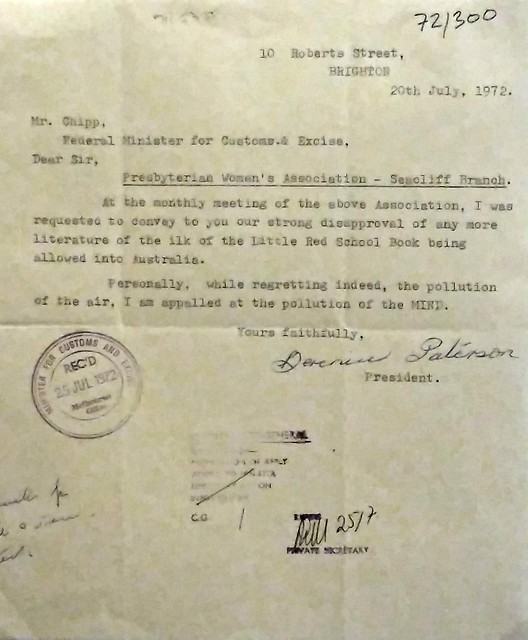

I've been listening to interviews with Australians who lived through the Great Depression. They tell of how they got by without wages. This involved relying upon food vouchers and work for the dole, as well as the generosity of shopkeepers and others.

Today we have many young people attempting to survive without wages in the digital economy. They are contractors or 'support partners' for companies such as Foodora or Deliveroo. They often receive remuneration at subsistence levels and lack almost all the usual benefits of wage earners.

Like workers who lived through the Great Depression, they are the victims of wagelessness.

Unusual for my generation, I experienced wagelessness when I was was in my twenties. A component of my studies for the Jesuit priesthood included full-time 'unwaged' work, as a secondary school teacher, and then in the media.

I received board and lodging but no payments. I did not have or need a bank account. Technically the work attracted a stipend (or a wage in the case of my ABC media work). But I did not see either because the funds went directly to the community.

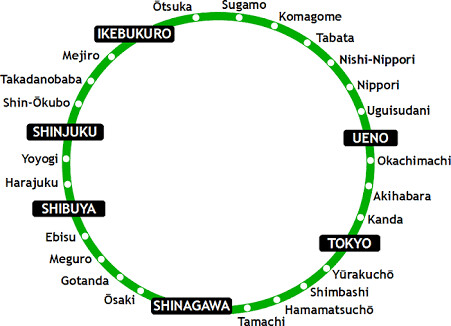

At the time I didn't see the need for an income other than a little 'pocket money' to allow me to go to the movies or get a train out of the city for a bushwalk on a Saturday.

But we all need to build financial wealth to provide a secure future for ourselves, and our family if we have one. The way to do that is to receive not only a wage, but a wage that increases exponentially.

I was lucky that I received a proper 'growing' wage once I left the Jesuits at the age of 30 and, almost 30 years later, have financial security.

The wageless of the Great Depression eventually got jobs, and at least some made up the lost ground. But uncertainty remains for younger people today, including the wageless and those with stagnant wages. What kind of future will they enjoy?