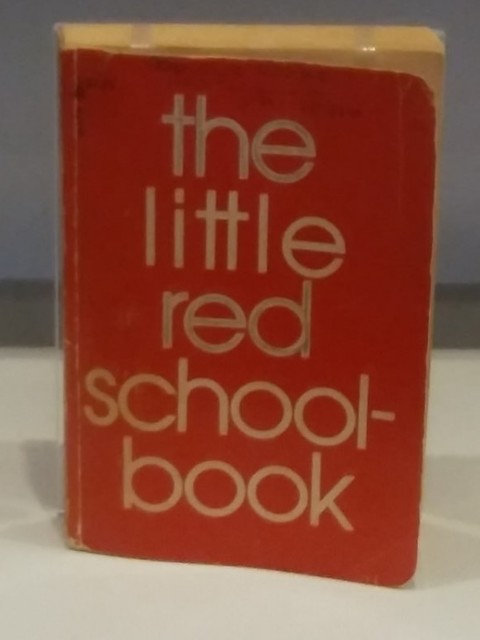

While spending the weekend staying with friends in Canberra, I visited exhibitions at Old Parliament House and the National Archive. Among the National Archive's current featured exhibits are documents related to The Little Red School Book.

Publication of this book was the subject of intense debate in Australia in 1972. It was banned in several countries but the Federal Minister for Customs and Excise Don Chipp eventually allowed its publication here.

The book's Danish authors encouraged school students to use their initiative against what they portrayed as the authoritarianism of the time. School teachers and other adults needed to be regarded as 'paper tigers' who 'can never control you completely'.

Discussing school education, the authors criticised the majority of teachers who 'think it's unnecessary to explain to their pupils why they must learn certain things'. With regard to sex and drugs, the issue in the minds of the authors was safety, not morality (i.e. harm minimisation). They emphasise technical explanations and advice about the risks of drug addiction and STDs.

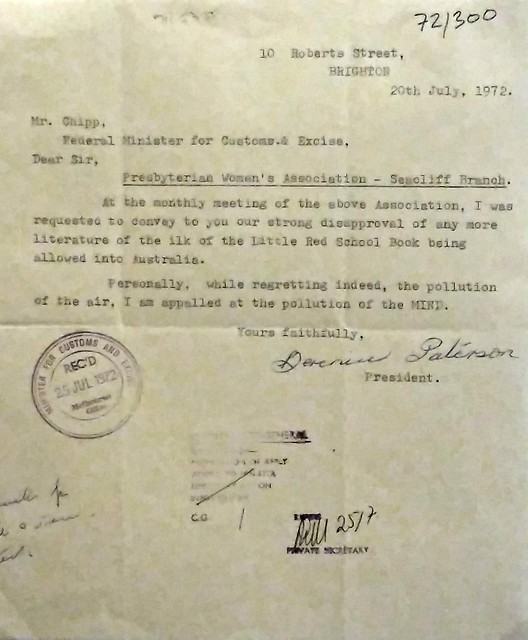

Documents in the National Archive exhibit include a protest letter from the president of an Adelaide branch of the Presbyterian Women's Association, who wrote that she was 'appalled by the polution of the mind' represented by publication of the book.

Another correspondent, from South Yarra in Melbourne, commended the Minister for resisting the protestors, who'd sent 'unsigned filthy notes ... worse than the publication that they are complaining about'.

I was drawn to the exhibit by a recollection from when I was in Year 7 at high school. It was 1972 and there was a rare non-conformist Christian Brother who quietly lent me the copy of the book that he'd managed to source.

As a 12 year old, much of it went over my head. But I remember perusing its content and writing a review to enter in a book review competition being organised by the school librarian. I won the competition because mine was the only entry. I'm not sure how the librarian managed to avoid censure from the principal, but that wasn't my concern.

Now when I think of the furore over The Little Red School Book in 1972, I'm inclined to compare it to the recent debate over the controversial Safe Schools Program, which in its own way is also designed to foster student responsibility and to avoid conflating safety with morality.

In contrast to their Coalition forbears who debated and approved The Little Red Schoolbook 45 years ago, it seems that members of today's Federal Government have shown a conspicuous lack of backbone in yielding to pressure from the right wing and acting to gut the Safe Schools Program.