It occurs to me that I don't really organise my day. Instead one or two particular circumstances give it a shape, and that may or may not help me to achieve goals for a given 24 hour period.

During my recent five week stay in Tokyo, my bed was a thin foam mattress on the floor. It was comfortable for sleep, but not to sit up and look at the screens of my tablet and phone.

So when I climbed into bed, I fell asleep almost immediately. When I woke up, I got up and went for a healthy eight kilometre power walk around the lake. I avoided the discomfort of being before a screen and so did not read and write in bed.

That was good, especially if there's truth in what they say about looking at screens in bed being detrimental to our general health and wellbeing.

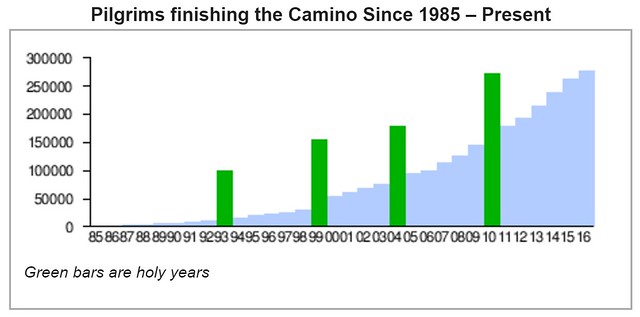

The sleep data in my Fitbit app showed that I was getting up to an hour's more sleep than when I'd been in my screen friendly bed at home. Comparing the 'before' and 'after' graphs (above and below) shows that staying away from screens in bed puts me on the cusp of being in the blue 'recommended' zone for my age group.

But it was not entirely good. What I'd done previously when I woke up was to research and write my blog. Doing the blog was no longer a natural wake up activity and instead became something of a chore. I'd have to choose to write later in the day and it would compete with other enjoyable activities such as sightseeing.

Nevertheless when I returned home to Sydney, I made a new rule for myself. No screens in bed. As a result, I've maintained my improved sleep patterns. Instead of walking around the lake in the morning, I've been exercising at the gym, something that had fallen away in the winter months before I went to Tokyo.

The blog writing is having to compete with other activities during the day proper. But I take the view that it is something I need to nurture like a plant that has been moved from one part of the garden to another.

But whatever happens, it will then be shaken up once more, when I transplant my life to another city for two months from early October.