Yesterday I drove with my sister to the southern Kent coastal city of Folkstone, where she had a work commitment. I remember Folkstone as the entry point on my first visit to England in 1993 after taking the ferry from France.

With ferry traffic having quickly declined after the opening of the Channel Tunnel in 1994, Folkstone ceased to be a significant port. The locals have been trying to regenerate the city as an arts hub, but it was Sunday morning and there was little going on as I walked through its slowly expanding Creative Quarter.

We drove west along the coast through Romney Marsh, a sparsely populated wetland area which was formerly known as a smuggler's paradise. This took us into East Sussex and the historic towns of Rye and Winchelsea, being directed by our GPS along quite a number of narrow country roads framed by beautiful thick canopies of green vegetation.

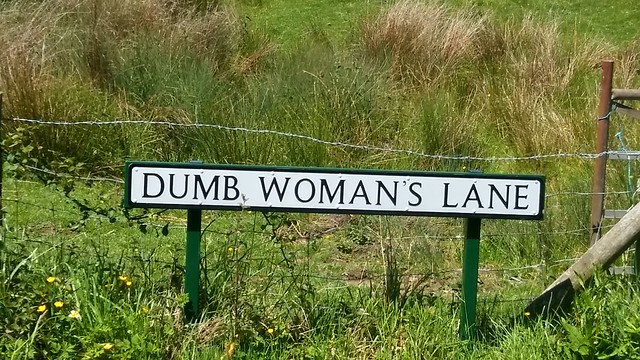

The most memorable of these, at least for its name, was Dumb Woman's Lane. I looked it up afterwards and - as expected - the naming has nothing to do with diminishing women. The legendary dumb woman was in fact mute, with the possibility that her tongue was cut out by smugglers she witnessed in order to prevent her from reporting their actions.

Our next destination was the small village of Burwash, which I knew was close to the former family home of a friend from Sydney. A further two miles down the road was Bateman's, Rudyard Kipling's home from 1902 until his death in 1936. It is now a National Trust property and we enjoyed the rest of the surprisingly sunny afternoon looking at the house and its interiors and walking in the large garden.

My friend told me that his family's home - an iron master's residence - was built with stone from the same quarry as Kipling's. Knowing him, I don't think he meant that as a claim to fame. In my eyes, it would be the opposite, for Kipling is one of those figures that I love to dislike.

I find it easy enough to be seduced by his genius for phrase making. But I'm much more mindful of his role as a triumphant champion of British colonialism, particularly in his birthplace India.

Earlier this year I'd been shocked when I listened to an interview that touched on some of the details of how the Britain trashed India's economy and cruelly exploited its people for its own economic and political advantage. It was with the Indian writer and politican Shashi Tharoor, who was promoting his new book Inglorious Empire: What the British Did to India.

Elsewhere Tharoor summarises his opinion of Kipling: 'Fine words strung together in praise of the morally indefensible'. This is a variation on George Orwell's criticism - 'He dealt largely in platitudes, and since we live in a world of platitudes, much of what he said sticks' - which we see echoed in today's politics.

Links: Creative Dumb Batemans Inglorious Tharoor Orwell