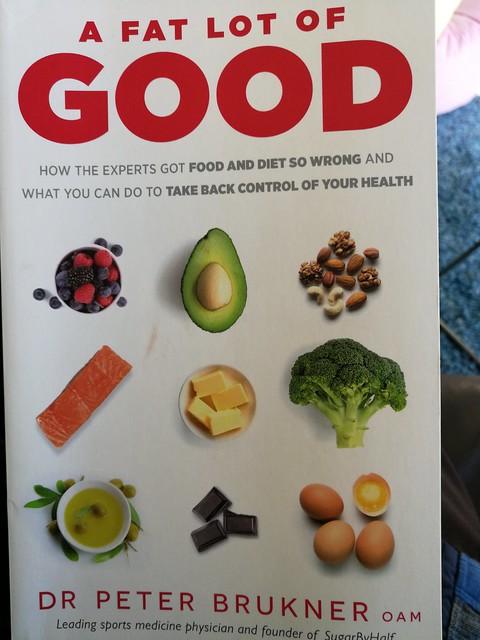

While I was working out at my Paris gym today, I was listening to a podcast of Geraldine Doogue's Saturday morning ABC radio program.

She was interviewing Irish professor Brian O'Connor on his book Idleness: A Philosophical Essay.

He was presenting idleness as a virtue, or at least a state of being that does not deserve a bad press.

The message is that many of us have to fill our lives with productivity because that's what our various insecurities demand. We have a craving for recognition and think that the only way of achieving that is to do something others will notice and give us credit for.

Was I working out in the gym because I want others to regard my body as easy on the eye?

That was certainly part of my initial motivation a few years ago when I first started going to the gym in Sydney.

But these days - particularly here in Paris - it's just one of my various states of being. Gym time is thinking time, people watching time, podcast listening time, and body stretching time.

Perhaps it's idleness. At least I'm not a slave to anything, which is what you are if you are preoccupied with working hard to fulfill the expectations of others.

That is perhaps where there's a difference between the gym in Paris and the gym in Sydney.

In Sydney you're more likely to see people thrashing themselves in the hope of becoming something. In Paris - the home of existentialism - it's more a matter of being. As I see it, they're already proud of who they are, and some outsiders choose to regard that as arrogance.

There's definitely a different energy, and our term 'work out' to describe what gym goers do seems strangely out of place in Paris. You're there because you're there. Of course you don't just sit around. You do pump iron and jump on the treadmill. But essentially it seems less about goal orientation.

My approach is much the same during the hours I'm not at the gym. I walk around the streets of the Marais every day with no particular purpose in mind.

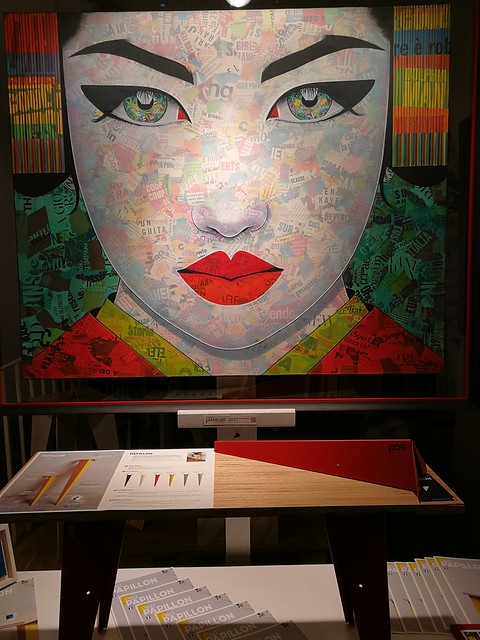

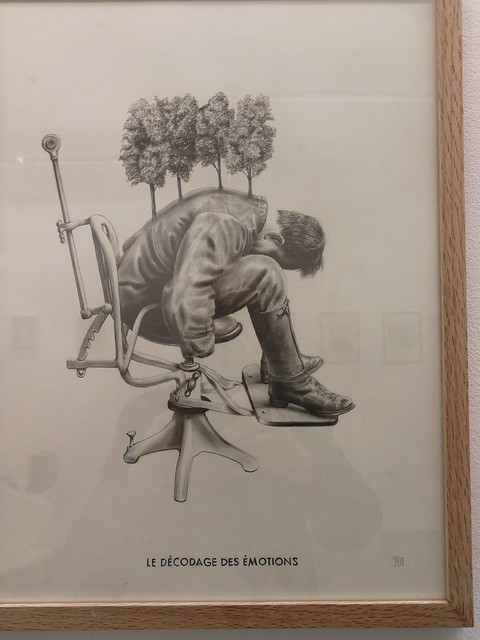

Today I entered five or six small art galleries and looked at the paintings on the walls and chatted to the attendants. In one sense I was idle and just passing time. But I don't feel the time was 'wasted' because I'm at home now with a stimulating mix of vivid images in my mind. A variation on the physical high I experience after my return from the gym.

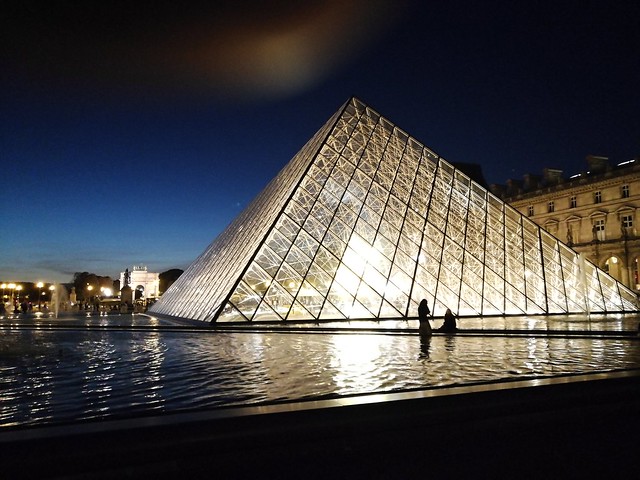

I sometimes wonder whether I should feel ashamed that I'm a few minutes walk from some of the world's most famous art museums including the Louvre and don't feel inclined to visit them. It's too much like hard work.