The big drawcards at this year's Sydney Film Festival included Nicole Kidman's latest The Beguiled, and Ben Mendelsohn's Una, which opens in cinemas tomorrow. To enter the screening of Una, I stood in a queue that snaked several hundred metres down Market Street and around the corner into Pitt Street.

They were both good films. But I found myself more drawn to Tom Zubrycki's documentary Hope Road, which is about raising money for a school in South Sudan. There was no queue to get inside for this one.

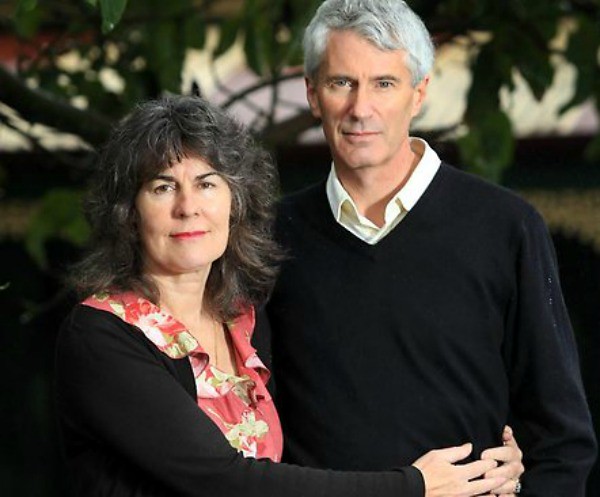

Zubrycki is now 70 and has spent many years perfecting his particular style of his observational documentary that is defined by the films' closeness to their subject.

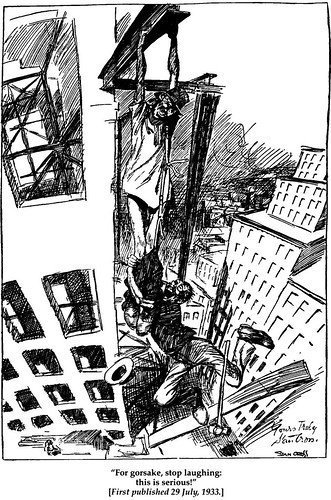

The subject matter may be worthy but I always find the execution quite nail biting, and often humorous in a subtle way that is recognisably Australian. I am reminded of the famous 'For gorsake stop laughing - this is serious' cartoon by Stan Cross that was first published in 1933.

Oddly this state of mind is characteristic of the White Australia era that preceded multiculturalism, yet Zubrycki's films reflect the vision of his father Jerzy Zubrzycki. Zubrzycki senior was a university academic credited as one of the main architects of the Australian government's multiculturalism policy that began in the 1970s.

But of course the genius of multiculturalism is that it was able to bring 'old' and 'new' Australians together in one magical harmony. That is exactly what happens in Hope Road, with South Sudanese refugee Zac Machiek getting together with three 'old' Australians including Zubrycki himself, to raise funds to fulfill his dream of building a school in his former village in South Sudan.

It's not promising, on a variety of fronts. They can't find a major sponsor for their walk to raise funds. One of the fundraisers has to have surgery for a brain tumour. Zac's marriage breaks up and he becomes a single father. The escalating war intervenes and the bricks they've bought to construct the school disappear.

Because the war is unlikely to end any time soon, the vision itself is challenged by the suggestion that scholarships might be more practical than building a school.

But Zac insists on the school and hope is their greatest resource. The film ends with plans for the school still a long way from realisation but the team's hope as strong as ever. As a film goer, it has you longing to see the sequel. As a human being, it makes you want to donate to help the project along.

Links: Zubryki Hope Road Donate