Years ago I remember a friend telling me that he'd just bought a house in a NSW country town for the price of a car. I've just done something similar with my purchase of a tiny room in the centre of Paris for less than the price of a car parking space in Sydney.

At the end of April, I spent three days staying in an airbnb maid's room near the Luxembourg Gardens. I'd just arrived at Charles de Gaulle Airport and I was headed to England to spend a month with my sister.

I thought to myself that I would like to own a room like this. I mentioned that in conversation with a friend in Lille who once worked selling real estate in Sydney. He's bought and sold several apartments in France, and he told me that it was easier than I imagined.

So with his help, I found online a five square metre room on the sixth floor of a building without a lift, for sale for 65,000 euros. It's in Châtelet in the First Arrondissement, a few minutes walk from either the Louvre or the Pompidou Centre. One of Paris's priciest locations.

I had my offer accepted in late June and signed the final papers and received the key at the notaires' office in Paris on Monday.

The room has a single bed, a shower, a toilet, a kitchen sink, a fridge, a wardrobe, and not much else. Just about all I need.

Five square metres is about the size of the bathroom in most Australian houses. I've stayed in capsule hotels in Japan in the past, and the room I lived in when I spent five weeks in Tokyo around August measured exactly five square metres.

Most buyers would probably classify the property as a renovators' delight. I could spend tens of thousands of euros gutting the room and engaging professionals to transform it into a designer showpiece. But I like it the way it is, at least for now.

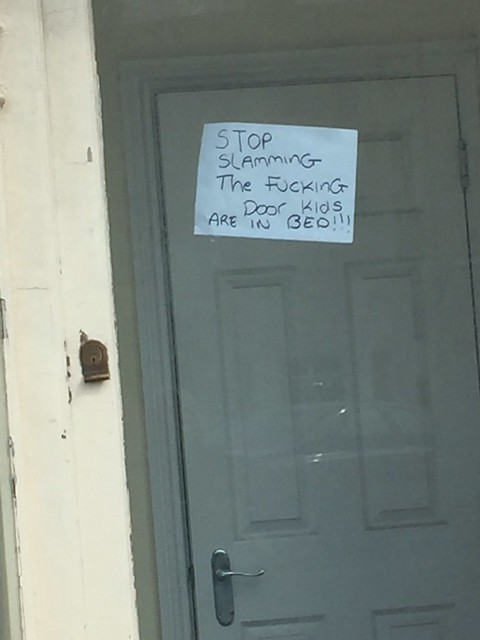

It's too small to rent legally, and the low purchase price means I don't have to earn an income from it. I will just spend a few months here each year getting to know Paris, and offer it to friends who don't mind simple accommodation for one person in a ramshackle building.

The notaire was intrigued and described the purchase as 'interesting', the same word an Australian lawyer friend used a couple of months ago. Before I signed, he also warned me of some of the things that could go wrong. For example the Marais - the Paris City Council - could decide that it is too small for human habitation and force me to rent it as a storage room.

It seems it's not wired to make it easy to connect to fast internet. So until I find a better solution than my current 3G mobile phone data plan, my online life will be in the slow lane. Which doesn't have to be a bad thing.