I remember where I was when I first heard that Catholics had overtaken Anglicans to become Australia's largest religious denomination numerically. I was with a group of Jesuits at a school in Adelaide in 1979 and one of them said that he had read it in The Australian newspaper.

However religious sociologist Gary Bouma contradicts that in The Conversation yesterday. He says it was 1986.

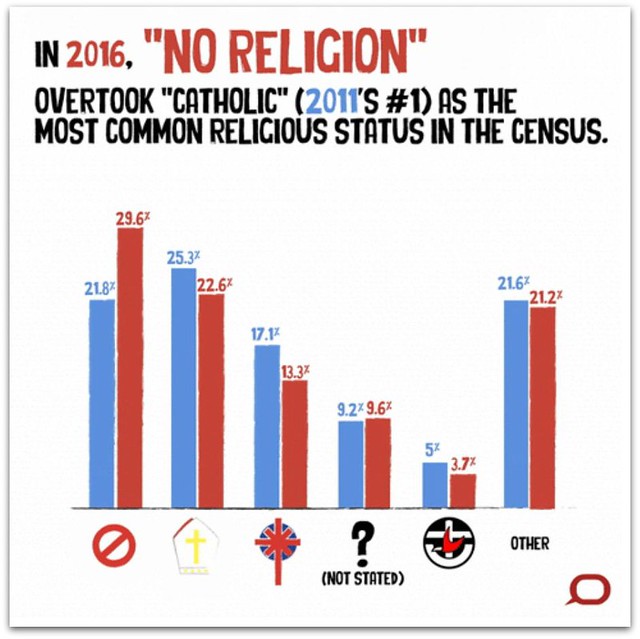

Whatever the year of that particular milestone, yesterday's big news was that the 2016 Census data revealed that Catholics themselves had been overtaken by a new group called 'No Religion'.

I think it is significant that it is not being mis-reported that atheism is the majority. At least not by Bouma, who gets it right when he makes this distinction:

'Declaring "no religion" does not mean that someone is anti-religious, lacking is spirituality, or an atheist. It means they just do not identify with a particular organised form of religion.'

It seems that this middle ground majority is reluctant to identify with the various mainly Christian denominations that are associated with their particular cultural or ethnic heritage. The 'Irish Catholics' of a generation ago now see themselves as 'no religion'.

They are the ones who count themselves out when Cardinal Pell and other conservative church leaders declare that being a Catholic is a 'package deal'. These leaders say that you can't be a 'cafeteria Catholic', which means accepting some teachings while rejecting others.

This view reflected these words of Pope John Paul II in 1987: 'A large number of Catholics today do not adhere to the teaching of the Catholic Church on a number of questions, notably sexual and conjugal morality, divorce and remarriage. It is sometimes claimed that dissent from the magisterium is totally compatible with being a "good Catholic", and poses no obstacle to the reception of the Sacraments. This is a grave error.'

Today the majority of Catholics including myself are cafeteria Catholics. I like to think that we are nuanced in our practice of the faith, combining conscience with guidance from credible moral leaders, whoever they may be. This group does not think twice about using artificial contraception or supporting marriage equality.

But its members are still concerned about issues of social justice. They send their children to Catholic schools believing they will develop a moral compass to guide them through life.

Even so, they won't be told what to do by the Bishops and other church leaders, whom they see as having covered up child sexual abuse to protect the Church. They look elsewhere for guidance on important issues that are not cut and dried, such as to Andrew Denton on euthanasia.

Denton is an entertainer who has become a credible moral leader because religious leaders have given up the ground. I don't agree with him on euthanasia but many Catholics do.

Pope Francis has shown the world what moral leadership from religious leaders can be about. Locally there is a handful of contrite church leaders with a credible moral and social message, such as Bishop Vincent Long of Parramatta. But it will take at least a generation before there is a possibility that the Catholic Church as a whole could make up the lost ground.

Last year I declared myself a Catholic on the census form because I think it's important for 'nuanced' Catholics like myself - and indeed my confreres from other Christian traditions - to claim our damaged religious brands in the hope that they can eventually be rebuilt to reflect the more inclusive spirituality that is currently described as 'no religion'.

Links: Bouma cafeteria Denton