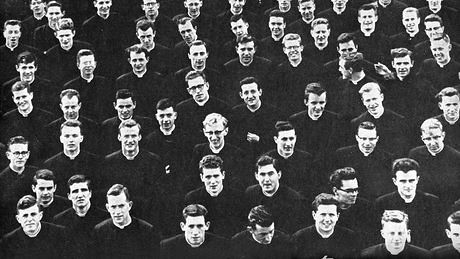

A friend recommended I watch this week's ABC TV Compass documentary 'The Judas Iscariot Lunch Part 1', which I did. It featured 13 Irish former priests who looked to be in their 70s, speaking candidly about their training and ideals as young men and also their own humanity and experience of celibacy.

They called their lunch club after Pope Paul VI's suggestion that those who left the priesthood were betraying the Church.

However I didn't think they harboured any particular bitterness towards the pope or the Church. They were just telling it as it was. The Church offered them a way out of the oppressive social and economic circumstances of Ireland at the time, as an alternative to emigration.

As one of them put it, 'a way of dodging growing up and dodging Ireland'. It's what they wanted at the time, and what they got.

So were they suggesting that they never grew up? Possibly. At least not until after they left the priesthood.

They referred to celibacy as a gift. As a priest, you either had the gift or you didn't. In other words, celibacy worked for some but not others. If it didn't, things went awry. 'People sometimes took to the drink. Loneliness became a big problem'.

Put simply, that is what happens if you're part of an institution that allows you to dodge growing up. Instead of the usual 'growing up' preoccupations that define the lives of most young people - working out relationships and sexuality - these trainee priests would be focused on listening to and obeying '12,000 bells over [up to] 12 years' of formation.

Of course the elephant in the room was sexual abuse, which I suspect they will discuss in more depth in Part 2. But in a way it was better they left that alone because it allowed the documentary to describe more dispassionately the culture of the Church that made the ground fertile for sexual abuse.

It reminded me of the term 'thick description', which was developed by the anthropologist Clifford Geertz in his influential 1973 work The Interpretation of Cultures. His idea was that the setting or context for particular behaviour is more meaningful than the acts of behaviour themselves.

Participant observation - such as the accounts of these ex-priests - is the key to evaluating a culture. This, he argued, was what anthropologists doing field research needed to pay close attention to.

I think that it is also crucial in achieving justice for church sexual assault victims. It provides a clear answer to the question of whether the blame lies with a 'bad' culture or 'rogue' priests. The implication is that if it can be established that a bad culture that produced rogue priests, the more appropriate course of action is redress from the institution that embodies the bad culture (i.e. the Church), more than locking up the perpetrators.

Too often media accounts let the Church off the hook by demonising the abusers. They focus on the experience of the victims at the hands of the abusers without painting a picture of the particular way of life that was the precondition for the abuse.